Citizen Science: What Do You See?

*SPOILER ALERT* If you haven’t completed the ‘What Do You See?’ survey in your CitizenMe app’s home feed, stop reading this! Come back when you have completed the activity to find out what it’s all about (it will be worth it!).

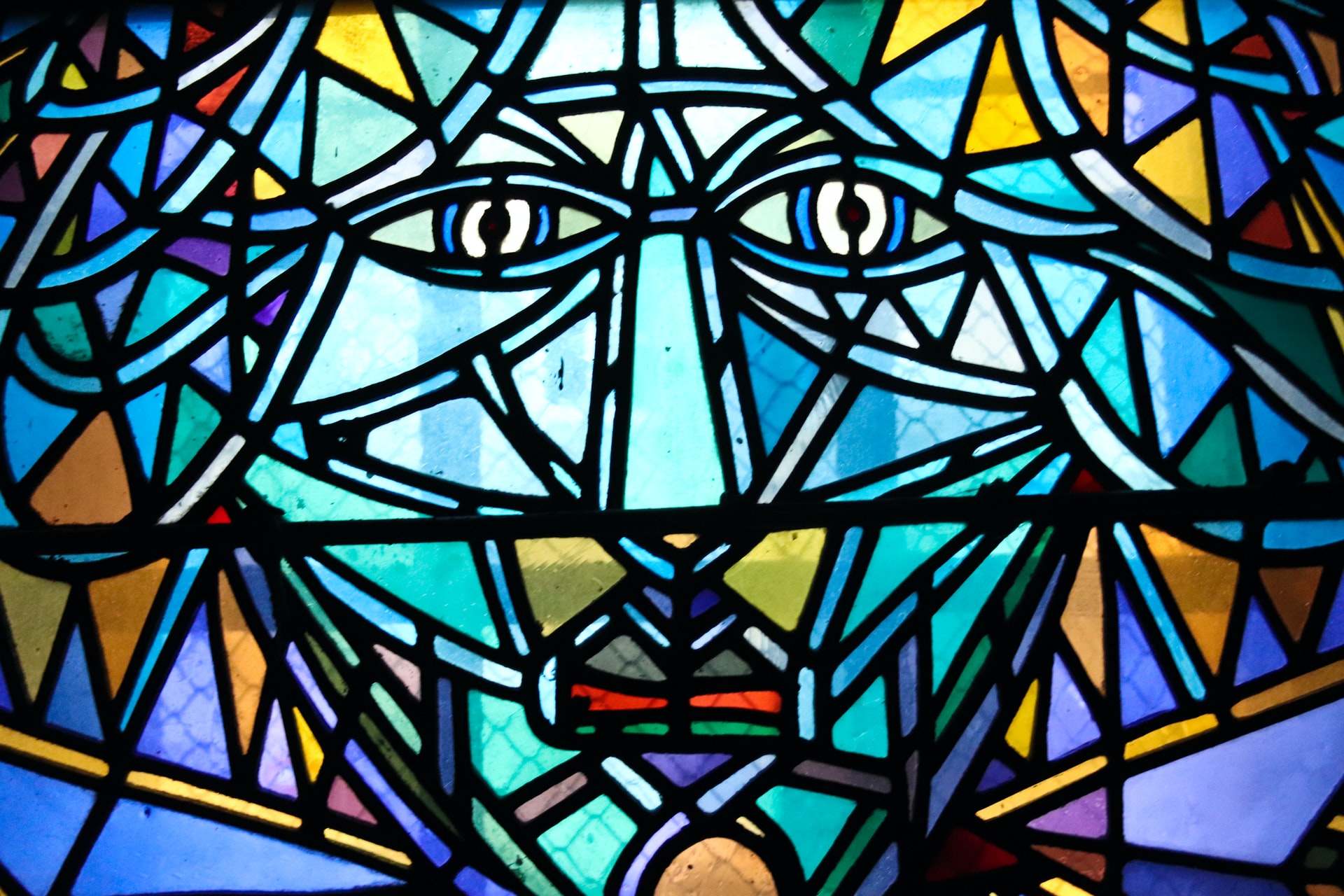

IN our recent ‘What Do You See?’ survey, it seemed we were simply researching people’s memory recall of a photo. The very first question we asked was how Citizens rated their memory recall: 39% rated their memory as ‘fair’ whilst an equally significant 32% rated theirs as ‘good’. Citizens were then shown a photo of a man and asked a series of questions about what they saw and also about other unrelated preferences. However, what we were really researching is a specific memory bias known as The Misinformation Effect.

What is the Misinformation Effect?

The misinformation effect is a well documented and researched memory distortion in which some individuals’ memory for an event (or photo!) can be changed after exposure to ‘misinformation’ or post event information, otherwise known as ‘interference’. We have to thank the cognitive psychologist, Elizabeth Loftus, among others, for her excellent research into this fascinating field of human memory. Her classic 1974 case study presented participants with photographic slides of a car accident: 32% of those questioned about the images saw erroneous broken glass when the word ‘smash’ was used, compared to 14% when the word ‘hit’ was used. It’s one example of how suggestibility, along with false presuppositions, leading questions, and ‘verbal contagion’, have all been used to manipulate memory recall.

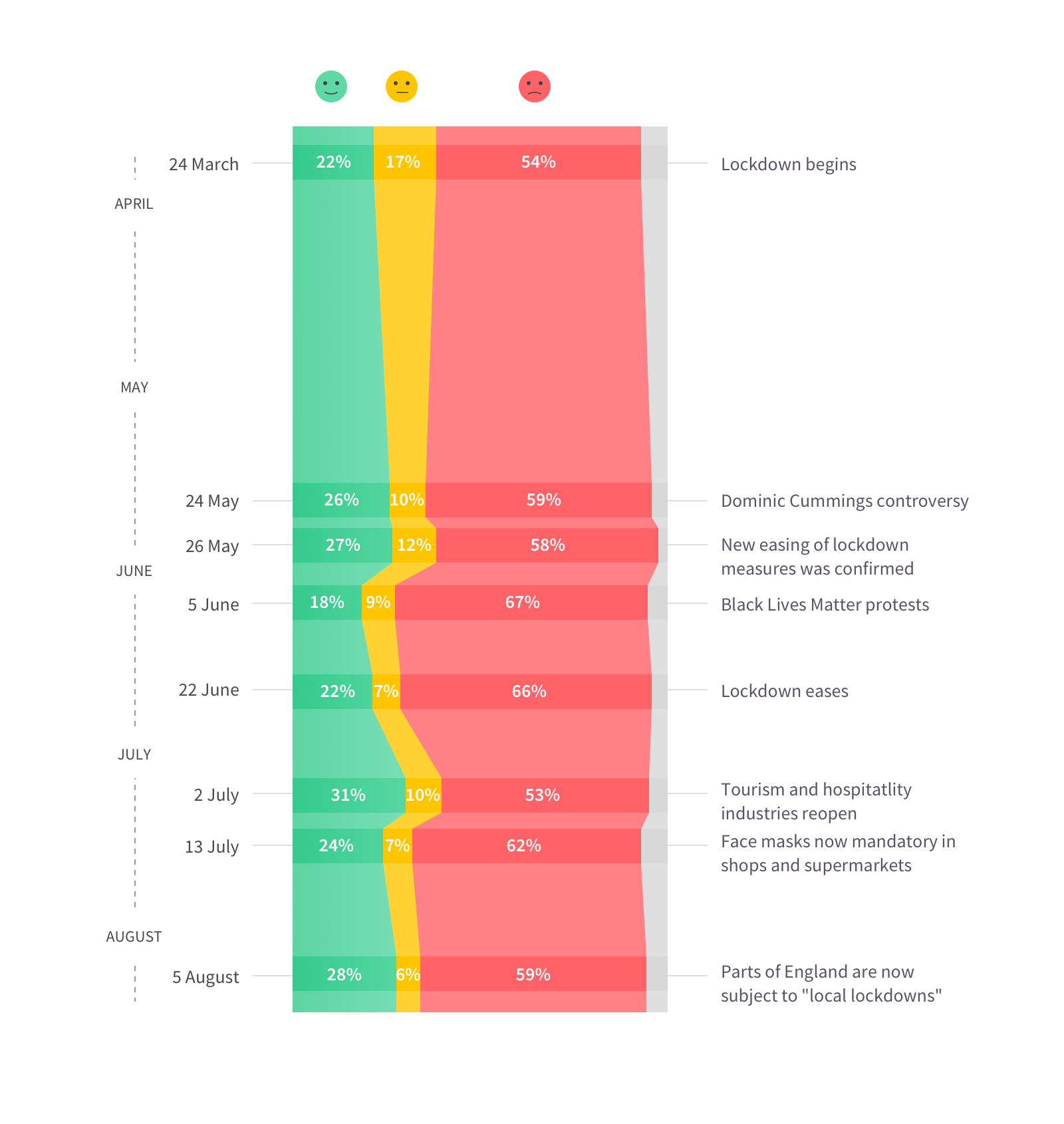

What were our findings?

In our survey, we were exploring whether the misinformation effect for face recognition is influenced by how that misinformation is delivered. Our first set of swipe questions on the photo shown made no mention of a beard, moustache or tattoo, and certainly there were none in the photo. We then asked four unrelated questions to take Citizens’ attention away from the task at hand, and then asked the question: “Do you prefer a beard or moustache?”. This was followed by another set of swipe questions, among them asking if a beard, moustache or tattoo applied to the photo, and also asking again if the man in the photo had brown or blue eyes. When asked for a second time the eye colour, there was no significant difference between first and second responses. However, significantly, in the second round of swipe questions, 11% of Citizens saw a moustache, 11% saw a beard, and 6% saw a tattoo even though the man had none of them!

What causes the Misinformation Effect?

A number of factors influence the misinformation effect. One is social context - a post-event conversation with fellow witnesses of a crime will affect some people’s recall of the event. Another is how people encounter erroneous information – visually, aurally, written, and semantically. Timing is also important. Loftus and her fellow researchers found the misinformation effect more likely to occur when exposure to misleading information happens after the memory of the event or image has diminished. This is why, as time was limited in our survey, we asked four unrelated preference questions as a means of ‘interfering’ with Citizens’ memory by taking attention away and refocusing it elsewhere.

Researchers have also discovered that the misinformation effect is greater if introduced immediately before a final test rather than just after the initial event. This is why we asked the question: “Do you prefer a beard or moustache?” immediately before using suggestibility as a means of misinforming when asking if Citizens saw a moustache, beard or tattoo. Repetition - repeating the same type of misinformation in the same modality (e.g. written) – also affects recall of the original information. Finally, age, personality, and people’s trust in their own memories are distinguishing factors. Certainly, our findings seem to support some of these factors were at play when a notable percentage of Citizens recalled features that were not there.

So why is this important to you?

This activity is a simple but effective showcase of how ‘misinformation’ can be used to influence your understanding of what you have seen, read or done in the digital world.

I hope you have enjoyed our simplistic but interesting research into memory recall and The Misinformation Effect.